I first saw the boxes of prints, negatives and contact sheets that would become the John Deakin Archive on the floor of Bruce Bernard's flat in Kings Cross in late 1988. For several hours that wintry afternoon we sat looking at hundreds of photographs of Soho artists, writers and characters, Parisian and Roman street scenes, industrial sites, graveyards, doorways, gates and graffiti, all shot with Deakin's unvarnished eye for the subtlety of his subjects, awash with inky shadows and feathery light, images of eviscerating uncertainty, others carelessly acute. Bruce had curated a small John Deakin exhibition titled "The Salvage of a Photographer" at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1984, but had been unable to raise much interest in the photographer's work since.

Shortly after John Deakin died in 1972, Bruce Bernard was given the dubious honour of guarding his life's work by serendipitous accident, and the story has become a kind of legend for those related to the archive. The story has it that Bruce and Francis Bacon went to Deakin's Soho flat to clear out the remainder of his belongings. There they discovered a pile of old boxes of Deakin's photographs, contact sheets and negatives. Although I never asked Bacon for his version of the story, Bruce said that when they found the boxes of photographs, Francis insisted Bruce look after them. Whenever Bruce related the story, he would imitate Bacon's remarks with a faint kicking motion with his foot, as if to shoo Deakin's uneasy legacy back out of sight. Without Bruce Bernard, Deakin's artistic vision simply would not have survived.

Bruce Bernard brought John Deakin's photography to life for me. He too was part of the same British post-war artistic milieu that John Deakin inhabited, often reflecting the epoch's nuanced ideals, its honourable creative failures, the quiet triumph of cultural values slowly gaining significance after years of being ignored.

Although some Soho survivors tended to dismiss John Deakin as a loser, in his work I saw a mordant artistic consciousness of a photographer whose empathy with his subjects transcended his personality. Many I spoke to remembered Deakin as a chippy little chatter box. Rejection does funny things to gifted people; Liverpool born Deakin didn't have much going for him in the first place.

Some of Deakin's sitters disliked him so descriptively that the extraordinary penetrating stillness typified in many of his portraits could well be because he'd literally bored them rigid. Could these dismissals also suggest the class consciousness still in play in the post-war arts scene? In spite of the compelling force of Deakin's work, it is possible that out of bohemia's own self loathing, his lack of personal charm justified the neglect of his photography as yet another ignoble failure.

From the moment I first saw his images, I felt that Deakin was a stunningly prescient photographer whose highly accomplished work was severely at risk of being written out of the history of British photography unless something was done. To me, his appeal lay in his captivating artistic vision, not his lack of popularity in the bars and clubs he drank in. So when five years later Bruce offered us the archive to buy for the collection, we jumped at the opportunity. Here was a chance to uncover an important layer of London's artistic history, to drill into 1950s Britain's quiet dreams and disappointments, to learn from Deakin's undiluted photographic aesthetic and to help reposition his artistic reputation in the UK and abroad.

British Vogue's archivist and curator Robin Muir had just started his first book on Deakin's photography when the boxes arrived at our studio. Robin has an ear for the revealing anecdotes surrounding Deakin's life and work, as well as a professional, confident, unconventional eye for curating photography. His essays on Deakin's life and work has set a new standard for photographic history writing. We were blessed to have him accompany us on the journey of cataloguing and preserving Deakin's work.

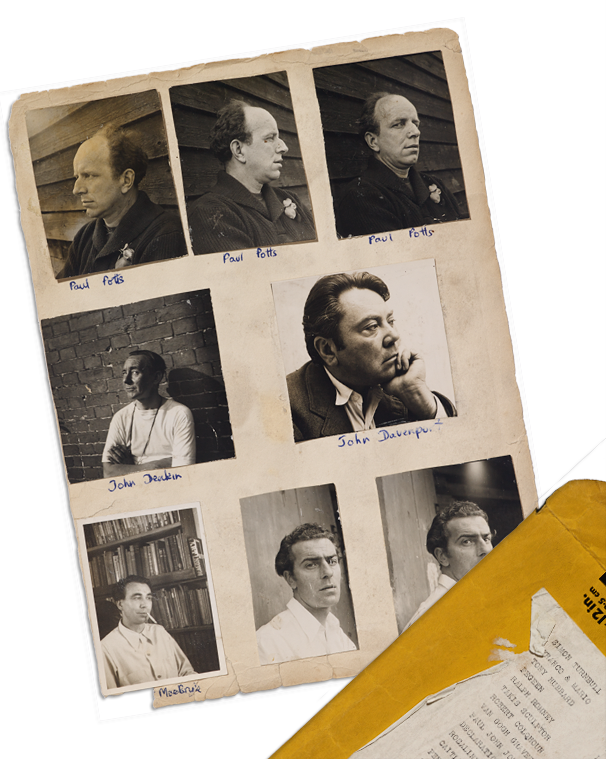

Over the next eight months Bruce came to work several days a week identifying the characters, settings and histories of Deakin's subjects sorting through boxes spread out on a long tailor's table. Image after image elicited vivid anecdotes, soft narrative associations, recollections of ancient feuds and bitter rejections, memories of hushed conquests and celebrated accomplishments. Imagine the strange joy of learning to listen with one's eyes, at the elbow of an expert whose fascination with photography's indisputable truths was expressed in murmured asides, strong solemn silences, chuckles, loud and soft sighs playing like muted piano keys alongside a scale of ascending ad descending moans. As he talked, Bruce would pull out images to illustrate his point. It was an experience of being part of a weather of audio and visual emotions. As his eyes alighted on unfamiliar images, glimmers of recognition dawned into remembrances of the lost souls, deceased friends and living artistic heroes of his own youth. Some days made him sadder than others.

Whenever Bruce or Robin arrived, they'd be anxious to show their newest discoveries. Their joy was infectious, and tremendously important in the archival process. When our assistant Ohma Oxley unearthed Deakin's exquisite image of the Roman girl in a mask, it seemed to mark a new kind of permission in our relationships with his photography; fresh eyes exhumed welcome digressions.

Modern cultural history can sometimes reflect unrelated collisions of convenience, feathers of meaning sticking to the floor, others fluttering beyond reach. For some years, it seemed that Deakin's neglected work may be understood as a response to photography's artistic uncertainty, perhaps even his own. So it was a thrill to see such reticence overturned when Charles Saumarez-Smith invited Robin to curate a retrospective of John Deakin's work at the National Portrait Gallery, saying "the National Portrait Gallery can be responsible for an appropriate act of restitution by ensuring that Deakin's photographs are not forgotten..."

Even so, it was assumed the exhibition would be modestly received, a polite aversion to disappointment proved wrong from the moment the show opened. Crowds of noted Londoners and fabulous nobodies thronged into the halls of the gallery to see John Deakin's work hanging in the great institution for the first time. On the walls, new prints hung alongside crumpled, torn, trampled and paint splattered historic prints, opening new pages of lost stories.

Outside, on the gallery steps that overlook Trafalgar Square, I paused to chat with Lesley Lewis - one of the owners of the French House, a pub which had played host to Deakin's drinking life as well as more recent displays of his photography. She told me the bar was so empty that night, she'd come the short distance to see what all the fuss was about. "You've got all my punters here!" she said.

When the John Deakin exhibition finally closed, attendance had broken previous records for the better known photographer Richard Avedon's retrospective. John Deakin had gained his rightful place in the history of British photography at last.

Jane Rankin-Reid, December 2013